Tiong Bahru - 'Hollywood of Singapore'

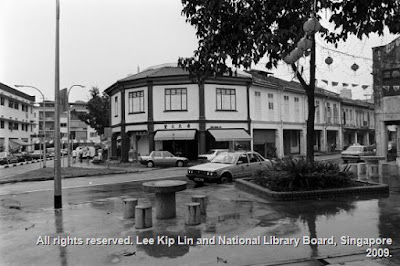

The building at the junction of Kim Pong Road and Tiong Bahru Road, same location at different times (photos above & below).

Till the mid-1950s the streets were still lit by pre-war gaslights, most of which failed frequently because the pipes had been damaged by bombing.

How much do I know about Tiong Bahru on this blog .

There are many historical information and nostalgic stuff to learn from Tiong Bahru where I used to roam during my childhood in the 1950s. I was then staying at Jalan Bukit Ho Swee after the Bukit Ho Swee fire in 1961.

With the help of the resources and research at NewspaperSG, I discovered an old newspaper published 35 years ago, I learnt that Tiong Bahru was once known as the "Hollywood of Singapore".

"Tiong Bahru - From slum to fashion hub of the 50s" by Jackie Sam, staff writer of Singapore Monitor on 9 September, 1984.

To young Singaporeans the pig farms off Ponggol are out of sight, even if the smell is not. To an older generation, pig farms used to be right in town.

In Tiong Bahru which is one of these rare Chinese-Malay names meaning "New Centre."

The older Singaporeans say tiong was originally the Hokkien Huay Kuan cemetery in the neighbourhood. The homonym tiong meaning "centre" was adopted after the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) estate was built in the late 1930s. It wasn't nice to call the new estate "New Cemetery."

Tiong for cemetery was in common usage amongst the peranakans (Straits-born Chinese) who settled on the fringe of the General Hospital towards the end of the 19th century. A big chunk of land was owned by the merchant brothers, Sit Wah and Sit Pai: Chinese sources say part of the district was named after Sit Pai which the colonials corrupted to Sepoy. English sources say it is derived from the Sepoy Lines where the Indian sepoys lived in quarters.

It was Sit Wah who built the row of two-storey terraced houses on Eng Hoon Street which leads to the hospital. The houses still looking in good shape, were the only brick houses there until 1937.

It was then alongside the track running through villages, the cemetery and vegetable gardens into the interior. Along this track which is now Outram Road-Tiong Bahru Road, farmers carried their produce in the pre-dawn hours for sale in town.

Sit Wah had Eng Hoon Street covered with granite chips. As a result the rickshaw pullers refused to take passengers across this stretch of road. Lee Boon Eng, 67, a retired clerk, gleefully recalls:

"Those babas were rich. They would have nothing to do with the poor farmers. Very proud people. So some people found satisfaction in watching them try to bully the rickshaw pullers into going up Eng Hoon Street and not succeeding. Big arguments all the time. Very funny to watch.

"But sometimes a particularly timid rickshaw puller would give way and then he would have to bend his legs and waddle slowly over the sharp rocks, barefooted. Poor fellow."

The rickshaw pullers didn't go into what is now Tiong Bahru, either. It was a small hill then and no rickshaw could be pulled up Or Chye Hng the old Hokkien name for Tiong Bahru.

The name means "yam garden" from the tuber grown there in large quantities to feed pigs here. And bean curd manufacturing. The two always went together because the jacket of the soya bean boiled with chopped yam leaves made good pig feed. Those days that was all the pigs had," Mr Lee says.

Huts dotted the undulating land. All the farmers were Hokkien, living in relative peace save for the occasional secret society battles they had to take part in. But these battles were fought elsewhere.'

"It was only after the war that young gangsters fought all over the place. In those days secret society people were rather like gentlemen. Whenever there was friction, reports would be made to solve them. If it couldn't be settled, one side would say: "Right, we meet at such and such a place, at such and such a time." That was all. And the battle ground would always be neutral territory away from each other's home ground. Of course, also as far away as possible from the authorities.

"Each side would not know how many men his opponent would muster. Or what weapons they would bring along. Too bad if one side miscalculates, So, before the war, it was very peaceful in Or Chye Heng" Mr Lee said.

The population of Tiong Bahru grew rapidly with the great influx of Chinese in the early years of the century. With many women now coming in, a lot of them began to settle in Singapore permanently. The town was so overcrowded the colonial government decided new housing would have to be provided.

In 1927 the SIT, forerunner of the Housing and Development Board, was established. But housing was only one of several functions and not the most important. Its resources were also limited and spent mainly on creating backlanes and reconstructing old shophouses.

It only started building single storey artisan's quarters at Balestier in 1932. But in 1936 it cleared Tiong Bahru for Singapore's first public housing estate. The SIT opted for flats completing 748 units in four storey blocks with 33 shops and upper-floor living quarters.

The first blocks were bounded by the extended Eng Hoon Street, Seng Poh Road, Eu Chin Street and Tiong Poh Road. This was, and remains, Tiong Bahru's centre. There used to be a high pillar, surmounted by a clock, on Guan Chuan Street where the road divider now ends. It was pulled down after the war.

All the new residents were wealthy men from elsewhere, moving in just before war broke out.

Like all other public buildings, these flats and shophouses were given camouflage colours in 1940. Underneath the staircases the SIT also built bomb shelters for the residents, each capable of accommodating six or seven people, seated.

Along some of the five-foot ways double-plank walls, filled with sand, were raised to provide additional shelters. In the open grounds (now car parks), U-shaped concrete structures without roofs provided extra shelters.

But when the Japanese began their drive down the Malayan peninsula, thousands of refugees went ahead of them, streaming across the causeway into Singapore - and many made straight for the much-publicised flats of Tiong Bahru.

The bombs of World War Two did little damage and flats could withstand quite a bit of bombing. Several felon these flats, most making large holes in the roof and two floors down. These were the first flats for local people.

So many refugees crowded in here that the flats looked like a huge, permanent air-raid shelter. It was described then as an "open city." And when the Japanese bombers were overhead, more people crammed into the shelters than expected.

The estate's garages, now occupied by a restaurant and the community centre, were chock-a-block with people and their meagre belongs. Even the pillboxes in Chay Yan Street and Moh Guan Terrace were crammed with refugees.

When the bombs were not falling women worked in make-shift kitchens which were 1.5m in height, in the streets and playgrounds.

Then came the sook ching. Purification through purge. All the residents were ordered to a large piece of vacant land on which the Tiong Bahru Market now stands. Unlike other concentration areas, it was not properly blocked off and there were not many Japanese guards around.

"The Japanese just roped off a large square. At the time I thought it looked exactly like Sports Day at school. I think Tiong Bahru was very lucky, very few people taken away to be shot.

"When I got there a few hundred people were already inside. But no guards. So we could leave at any time. That evening I went home. Next morning I went back. Most of us didn't wnt to offend the new conquerers. There were all the stories of atrocities from China.

"We were told the Japanese needed labour to clear away all the rubble in the city. If that was all right. Nobody knew what was happening elsewhere on the island, but everybody was looking forward to resuming normal life.

"Next morning a captain came along, accompanied by a few local detective. He gave us a lecture. Singapore is now 'Shonan,' he said. All Singapore and all private properties now belonged to Japan. You people have now to listen to the Japanese. That's his lecture.

"Then we were all categorised. Businessmen one side, students another side, labourers another group, and so on. Some groups, like the businessmen went into lorries. Most of us thought: Ah, now the Japanese want to make them labourers, make the eat humble pie. Nobody thought they would disappear for good.

"I said I was a labourer. Then we had to file past a table where the detectives were seated. Got stamped on the arm and went home quickly.

"Next morning, the detectives were around again, telling everybody to report to Tanjong Pagar Police Station. Everybody in Tiong Bahru went. We got there by about 4.30 p.m., gathering on the vacant land beside the station. Used to be know as Trafalgar Street.

"Another captain gave us a very long lecture. All about Dai Nippon, great country, blah, blah, blah. Everything in Singapore now belonged to them. We must now be loyal to the emperor. Lots of threats. We would be executed if we didn't obey. Went on till 8 pm. Then we were told to go home. Nobody taken away. In all these years here, from childhood till now, I think that was the biggest event in Tiong Bahru.

"I refused to do any work. Many people didn't work. But later the Japanese ordered everyone to get a job or else be conscripted for labour, so I went to a godown around the corner to work as a payroll clerk for a Japanese factory making raincoats out or latex and old newspapers," Lee says.

By then all the open spaces of Tiong Bahru were overgrown with tapioca. The Japanese started a "grow more food" campaign. Most people took the easy way out and grew tapioca.

British prisoners-of-war were made to clear the nightsoil and refuse of Tiong Bahru. "People came out to outwit the Japanese whenever the PoWs came by. The guard always walked ahead. Behind him the residents would push bread, yue cha kway and cigarettes into the hands or pockets of these PoWs. Anyone who got caught would be beaten up. Still, every day residents did it," Lee recalls.

The flats came under the jurisdiction of the Custodian of Enemy Properties and looked after by the old staff of the SIT.

"The problems during the Occupation were the same as pre-war and immediately after the war: illegal brothels and gambling dens," says one of the men who had to look after the place.

It took a few years after the war before the SIT refurbished them, removing the camouflage colours and repairing the bomb damage. Then it quickly acquired what one writer called "its most striking feature: smugness." Behind this description was a touch of envy. There were so many homeless, so many others crammed into dilapidated shophouses that many were jealous of those living in these flats.

By 1954 there were 2,000 units and more shophouses. This completed the Tiong Bahru "district" bounded by Tiong Bahru Road, Kim Tian Road, Jalan Bukit Merah and the Singapore General Hospital.

"Looking at it now it is hard to believe that Tiong Bahru was known as the Hollywood of Singapore and a fashionable corner of the island," says Monitor journalist Sit Yin Fong for whom Tiong Bahru was an important part of his newspaper "beat." High-rise living was then regarded as an American lifestyle and that was half the explanation for calling it "Hollywood."

The other part of the explanantion was the "avant garde" lifestyle of many residents. They were mainly cabaret girls and mistresses of rich towkays. The women went about in the latest western styles and cheongsams with daring thigh-high slits.

"Mahjong day and night. The cabaret girls had nothing to do in the day so mahjong was very popular," says Sit.

Tiong Bahru acquired its reputation soon after its completion. Its proximity to the Great World Cabaret and the red-light district of Keong Siak Road had to do with this as well.

But these flats were meant for the poor. "A lot of these tenants just rented out rooms or even the whole flat to professional men or rich towkays who kept their mistresses there.

"For these prominent people it was an ideal hideaway. You could go there by taxi and slip quickly into the dark staircases. Some of them had as many as three or four mistresses tucked away in the estate.

"Every night there were many taxis coming in, dropping off people. And there was a big coffee shop opposite the market that was a meeting place for young Romes. Teddy boys, they were called.<

"The gangsters also met met at this coffee shop for talks and negotiations. No fighting.

In the 1960s, as low-cost housing was carried out on a colossal scale, the problem began to ease. The squatters moved out; the surrounding areas developed. A no-nonsense application of the anti-secret society Temporary Law Provisions put a lot of the gangster leaders behind bars; crimes dwindled. The outdoor hawkers moved into new centres elsewhere.

In 1968 the flats were sold to residents. By that time Tiong Bahru had acquired a middle-class sobriety. But it continues to stand out architecturally and socially. The surrounding housing estates are built much higher and their occupants less sophisticated.

The market now serves mainly residents. But its foodstalls draw large numbers of nurses every morning, and office workers at lunchtime.

Photo of Gan Family outside Sit Wah Road on 1945

<Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew visit to Sepoy Line & Tiong Bahru

PM Lee Kuan Yew viewing exhibits after opeing $800,000 Tiong Bahru People's Auditorium at Seng Poh Road. Looking on are Member of Parliament for Tiong Bahru Chng Jit Koon (second from right) and other officials on 25 August 1979.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew Visit to Ananda Metyarama Temple at Jalan Bukit Merah